The Social, Legal and Ethical Implications of AI for Manufacturing

After 70 years of being ten years away, AI has finally started to be deployed across many application areas. Concerns have been raised about the social, legal and ethical implications of these deployments, and this article provides an overview of the issues that arise in the specific area of AI for manufacturing, such as liability, worker privacy, autonomy and the social and economic implications of even greater automation of manual labour.

Legal issues: Safety and Liability

Industrial machinery has always been dangerous. Much of the development of workplace health and safety law has followed on from the development and deployment of new manufacturing machinery. In the second half of the twentieth century, the introduction of industrial robots presented new challenges. In 1992 an ISO standard (ISO-10218) on safety and industrial robots was published, and has been regularly updated since (the latest adopted version is from 2011 but it is currently under review). Much of that standard is based on the idea of robots being “encapsulated”, i.e. having a physical volume in which it operates that humans only enter when the machine is powered down. Other elements include visible and accessible “emergency stop” buttons which may be activated both from within and just outside the encapsulation area. The development of the “cobot” (collaborative robot) concept reduces or removes much of the encapsulation of robotic movement in operation and introduces risk of injury to people within the range of movement of robotic systems. AI control of cobots is proposed as one way of reducing such risks. AI applications that may be of use include computer vision systems to detect the movement of human bodies within the range of movement of the robot, multi-sensor information integration and interpretation to detect when human bodies might be harmed by robot movement or robot-controlled tools (tools such as laser or water jet cutters project force beyond the physical elements of the robot and tool). An additional standard (ISO/TS 15066) addresses these cobot safety issues [1]. AI control must not be regarded as a panacea, however, and the lessons from earlier industrial robotics experiences need to be retained in development of these new systems.

When something goes wrong, whether an industrial accident involving injury or death, the waste of resources from incorrect operation or simply the cost of a manufacturing system not being available to perform its tasks, then some person or organisation will bear the resulting costs. If equipment is faulty then the responsibility will lie with the manufacturer of the equipment, the maintainer of the equipment (which may be the manufacture, the operator or a third party), or the operator of the equipment (if they have misused it). Many AI systems are adaptive to their environment Indeed, that ongoing adaptability is often one of their key selling points. However, this gives rise to new questions about liability resulting from failure. The AI software is no longer produced solely by the programmers, and the question of the extent to which the operator can be held liable for the information the system uses to change its operations remain open questions legally so far. This is one of the reasons why the issue of “explainable AI” is relevant in the AI for manufacturing context (see, for example, EU-Japan.AI’s sister project XMANAI: https://ai4manufacturing.eu/project/) as well as in the more obvious areas of explaining AI decisions such as in a law enforcement [2] or security surveillance context [3].

Ethical issues: Surveillance

Quite a few of the applications of AI in manufacturing involve visual surveillance of the assembly line for monitoring of one or both of manufacturing equipment and product. Safety and security issues can also involve AI interpretation of visual monitoring of manufacturing premises. However, once surveillance equipment is installed, there is a general tendency towards function creep [4]. One of the obvious expansions of equipment/product surveillance is to worker surveillance, and another is from safety and security surveillance to productivity surveillance. While workers have a lower expectation of privacy in the workplace than as citizens in their homes or other locations, they do retain some expectations of privacy in the workplace [5] and these must be considered when managers of manufacturing facilities are considering the deployment of visual surveillance with AI interpretation of activities in view.

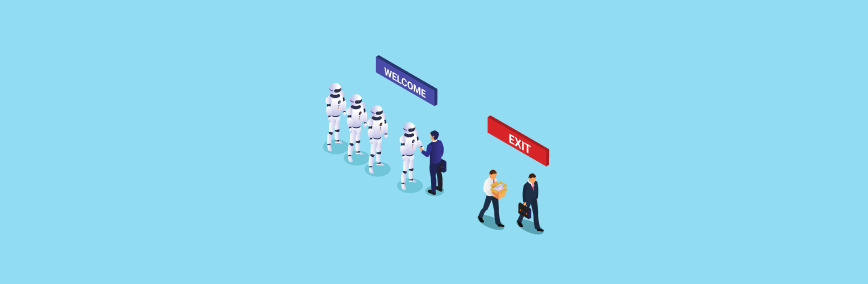

Social and Economic Issues: Rewarding Capital over Labour

Since the industrial revolution, there have been concerns about the development of new industrial machinery undermining the economic stability of workers by reducing one or both of the level of skill needed and the number of workers [6]. Although some [7] claim that the revolution in AI will not undermine worker conditions, salary or employment, there is a significant body of research papers by industrial economists which raise deep concerns about the impact of AI in manufacturing alongside many other areas of the economy. Few predict that all jobs will be automated out of existence, but there is significant concern about too many jobs in many sectors being automated away too quickly for the development of any significant new sector of the economy to develop to replace those jobs, unlike the previous wave of automation in manufacturing in the mid-to-late 20th century [8]. Those worrying about the potential impact of mass reduction in demand for employee work such as Furman and Seamans [9] suggest that a revolution in how economies work may be needed to prevent mass social disruption. Potential solutions have been proposed, including a Universal Basic Income or guaranteed government employment. Economic rebalancing such as taxes on Robots and/or taxes on AI systems could be used as one way to enable such policies to be enacted without completely abandoning current economic bases [9, 10]. Current government policies in areas as diverse as taxation, income support, industrial development, international trade and research funding allocation all play a part in this developing conversation about the future of work and paid employment.

In addition to economic concerns there are social and psychological questions about the value of holding a job for people’s self-worth and for social cohesion [11]. While earlier predictions about the future of work from the early or mid twentieth century optimistically predicted shorter working hours and greater leisure, the reality in the early twenty-first century has been of ever-longer working hours, for more limited pay and other benefits, and ever-increasing inequality in wealth, a significant part of which can be laid [11] at the door of government policies continually prioritising returns on capital investment (through taxation, industrial development and research funding policies) over return for labour. The impact of the CoViD-19 pandemic has brought many of these issues into sharp relief, with its enormous impact on increasingly inequality [12] but also highlighting the potential for government support of higher pay for less work through furlough schemes.

Author: Andrew A. Adams (http://www.a-cubed.info/)

Centre for Business Information Ethics (https://www.isc.meiji.ac.jp/~ethicj/epage1.htm),

Meiji University (https://www.meiji.ac.jp/)

References

[1] Lazarte, M. “Robots and Humans Can Work Together With New ISO Guidance”, ISO News, International Standards Organisation, 2016. [Online] Available: https://www.iso.org/news/2016/03/Ref2057.html [Accessed Dec. 10, 2021]

[2 ]R. Matulionyte and A. Hanif, “A call for more explainable AI in law enforcement,” 2021 IEEE 25th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop (EDOCW), 2021, pp. 75-80, doi: 10.1109/EDOCW52865.2021.00035.

[3] L. Viganò and D. Magazzeni, “Explainable Security,” 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), 2020, pp. 293-300, doi: 10.1109/EuroSPW51379.2020.00045.

[4] T. Wisman, “Purpose and Function Creep by Design: Transforming the Face of Surveillance through the Internet of Things”. European Journal of Law and Technology, 4(2), 2013, Available https://ssrn.com/abstract=2486441 [Accessed Dec. 14, 2021]

[5] I. Ebert, I. Wildhaber, J. and Adams-Prassl, “Big Data in the workplace: Privacy Due Diligence as a human rights-based approach to employee privacy protection”. Big Data & Society, 8(1), 2021. Available: https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211013051 [Accessed Dec. 14, 2021]

[6] K. H. O’Rourke, A. S. Rahman, & A. M.Taylor. “Luddites, the industrial revolution, and the demographic transition.” Journal of Economic Growth, 18(4), pp. 373-409, 2013. Available: https://www.academia.edu/30842410 [Accessed Dec 17, 2021]

[7] B. Dwolatzky, “The 4th Industrial Revolution Series: The Robots are NOT coming “, FirstRand, 4th April, 2021. [Online], Available: https://www.firstrand.co.za/perspectives/the-robots-are-not-coming/ [Accessed Dec 17, 2021]

[8] W. W. Powell and K. Snellman, “The knowledge economy,” Ann. Rev. Sociol., vol. 30, pp. 199-220, 2004.

[9] J. Furman and R. Seamans, “AI and the Economy,” Innovation policy and the economy, vol. 19, no.1, pp. 161-191, 2019.

[10] A. Agrawal, J. Gans and A. Goldfarb, “Economic policy for artificial intelligence,” Innovation Policy and the Economy, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 139-159, 2019.

[11] D. Acemoglu, and P. Restrepo, “The wrong kind of AI? Artificial intelligence and the future of labour demand,” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 25-35, 2020.

[12] J. Kaplan,”Billionaires around the world added $4 trillion to their wealth during the pandemic”, Business Insider, 3rd April. Available: https://www.businessinsider.com/billionaires-added-4-trillion-to-their-wealth-during-the-pandemic-2021-4 [Accessed July 9, 2021]